Rasputin is a Saint: A Response to the UOJ

On January 6, 2026, the Union of Orthodox Journalists (UOJ) published an article titled: Was Rasputin a Saint? This article — 3200 words long — is framed as an objective historical exploration of Grigory Efimovich Rasputin and his role in the Orthodox Church. However, due to pre-existing biases and historical ignorance by its author, Michael W. Davis1, the article fails in its purported mission, turning instead into a propaganda piece against one of the most slandered men in the history of Christianity.

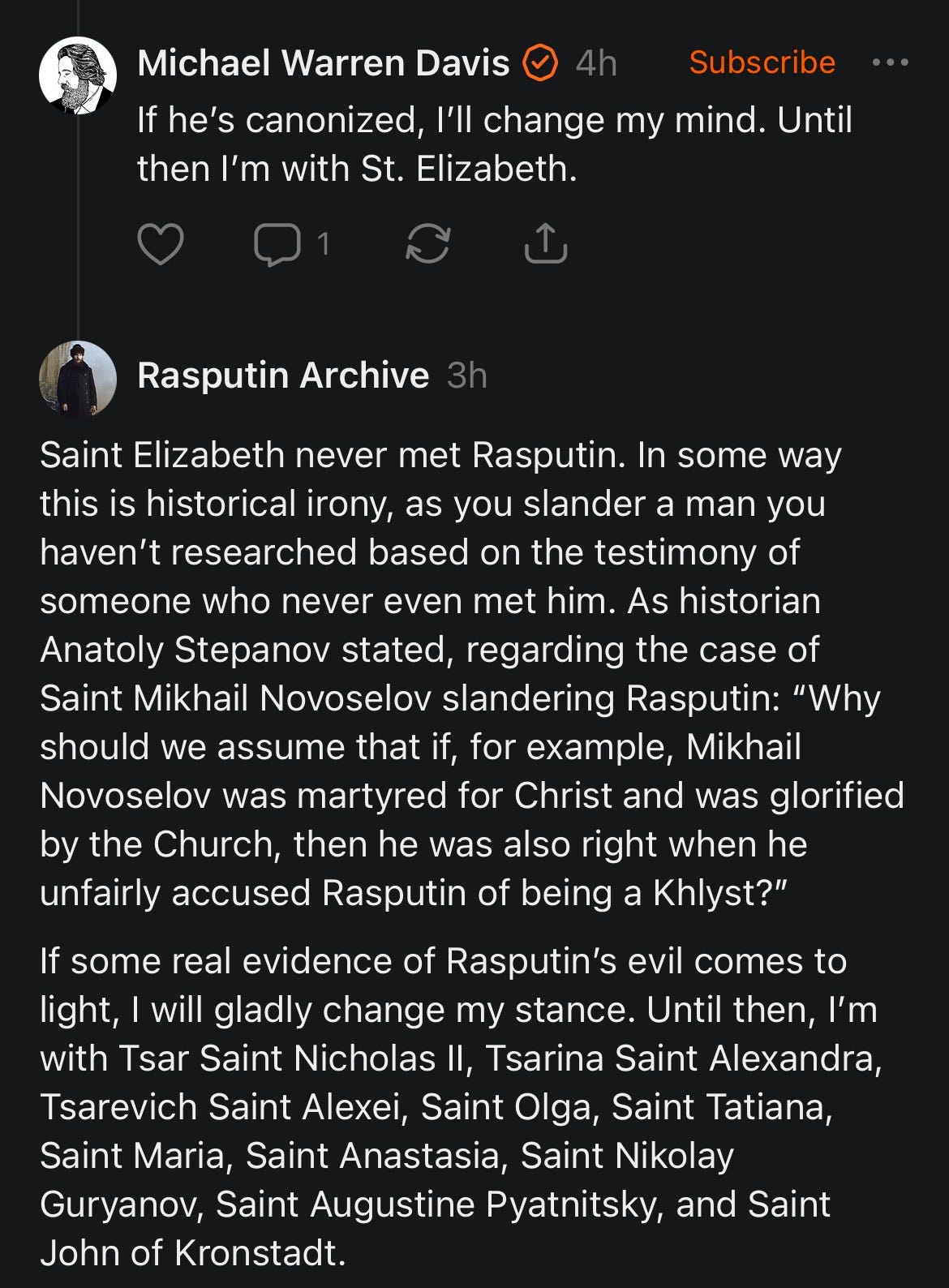

When our first article, The True Religion of Grigory Rasputin was published in September, 2025, Davis challenged our thesis, citing Saint Elizabeth Feodorovna’s negative opinion on Rasputin. This was followed by a quick and thorough refutation of his argument on our part, which he obstinately disregarded, saying he would rather stick with Saint Elizabeth.2 Davis insisted that our historical investigation about the real Grigory Rasputin was flawed, yet seemed to be ignorant on the subject matter months ago. On January 6, 2026, however, he published an extensive article on Grigory Rasputin, presenting himself as an expert on this character of Russian history. In fact, this article is — in his view — so authoritative that it ought to be considered “the final word on the matter”.3 This seems to be quite an unfortunate statement for those who continue to seek historical and spiritual truth, yet if the article is of such great quality, perhaps all previous historiography could be discarded. Regrettably, this is not the case, as the article is historically flawed. Hence, it will not be considered the final word on the matter by those of us who have dedicated years to exploring the life of Grigory Rasputin.

For this refutation, Davis’ article will be extensively quoted, identifiable by a black vertical bar on the left side of the screen. All of the text in the article has been quoted, every single sentence. Before addressing the arguments, the structure of the article must be considered. Davis does not use footnotes and hardly references the sources he uses for many of his claims. In the spirit of truth, I have found, shared, and debunked or contextualized the sources he failed to cite, as well as our own sources which I believe to be more historically reliable. After analyzing his quote selection, I believe that Davis has only read Douglas Smith’s book Rasputin: Faith, Power, and the Twilight of the Romanovs. While it is undeniably a historically rich book, it fails in many aspects, and anybody who wishes to have the final word on the matter of Rasputin must read more than just the introductory book on his life. With that in mind, let us explore the article and see what it gets right and wrong.

Was Rasputin a Saint?

Most of the “black myths” surrounding Gregory Rasputin are utter lies. He was not a sorcerer; he was not a Khlyst; he did not have an affair with the Tsaritsa. However, credible evidence from Orthodox bishops and contemporaries reveals him as a drunken womanizer, an influence-peddler who deceived the Royal Martyrs. Rasputin caused untold damage to the monarchy, which is why the Russian Orthodox Church has (correctly) refused to canonize him.

As I previously stated, Davis seems to be parroting his understanding of Smith’s book rather than engaging in objective historical analysis. His whole article could very well be re-written as a book review and would spare us the trouble of refuting him. Alas, he wished to call us out without naming us, and we had to respond.

Davis gets the “black myths” about Rasputin correct. He was not a Khlyst,4 a sorcerer, and most definitely did not have an affair with the Tsarina.5 However, he goes on to claim that “credible evidence from Orthodox bishops and contemporaries reveals him as a drunken womanizer, an influence-peddler who deceived the Royal Martyrs.” What that evidence is, we have yet to find out. At least Davis has dropped the facade of objectivity and will go on to slander Grigory Rasputin, stating that the ROC “correctly refused to canonize him.” This “refusal” comes from a corrupt commission which will be further analyzed throughout my response and can’t be considered binding or truthful in any way.

Recently, some Orthodox “influencers” (including friends of the UOJ) have become vocal apologists for Gregory Rasputin. A few are even calling for his canonization as a saint!

By Orthodox “influencers,” Davis probably means Anthony Westgate,6 James Delingpole,7 Dmitry and Conrad from WWN8, and of course myself, Rasputin Archive. It is unfortunate (perhaps even cowardly) to call us out and not name us. Perhaps if Davis’ readers had access to our work, they would critically analyze the existing historiography and make up their own minds.

A few are even calling for his canonization as a saint!

This is not that controversial. After Rasputin’s death, Tsarina Alexandra had a small book printed out titled “A New Martyr” in his honor.9 Tsarevich Saint Alexei said “There was a saint, Grigory Efimovich, but he was killed.”10 At the time of their martyrdom, each of the Romanov daughters “wore around her neck an amulet bearing Rasputin’s picture and a prayer by the peasant ‘holy man’.”11 Tsar Nicholas died wearing a cross gifted to him by Rasputin.12 Elder Nikolay Guryanov said that “Grigory is holy and a great Martyr before the Lord. His icons are needed; people have prayed before them, are praying, and will pray, and weep, as I do, weeping and praying before this image.”13 Veneration of Rasputin began right after his martyrdom in 1916 among the Romanovs and his close followers. This extended into the 1920s, where followers of Rasputin painted/wrote Icons such as the one below.

Nowadays, the veneration of Rasputin persists despite attempts to censor it, particularly in Russia among clergymen and followers of Tsar Nicholas II.14

The Rasputinists claim that Rasputin was slandered by jealous courtiers and Bolshevik agitators. He was not the cause of the Russian Revolution. On the contrary: he was the only man who could have saved the Autocracy. Instead, he became a sort of protomartyr, his death foreshadowing those of St. Nicholas, St. Alexandra, and their children.

But are they right? Let’s look at the facts.

Not to be pedantic, but the correct term is Rasputinite.15 In any case, it is correct that those who advocate for the historical rehabilitation of Rasputin claim that he was not the cause of the Russian Revolution. In fact, it was slander against Rasputin that led both directly and indirectly to the dissolution of the Monarchy.16 Davis proceeds to state “Let’s look at the facts,” once again framing this as an objective historical endeavor, which it is not. Throughout this response, it will be shown that rather than sticking to the facts, Davis allows anti-Rasputin and anti-Tsarist propaganda to form the basis of his article.

Before moving on to Davis’ first section on Rasputin, I would like to quickly point out something concerning. Davis, as has already been shown, is acutely aware of the work done by Rasputin Archive and others in the historical exploration and rehabilitation of Grigory Rasputin, the Romanovs’ friend. In fact, his whole reason for writing the article was the trend of “Orthodox ‘influencers’ (including friends of the UOJ) [becoming] vocal apologists for Gregory Rasputin.” This would suggest that Davis is familiar with the information shared by those apologists, meaning he has listened to the podcasts and read the articles, perhaps even engaged with some book recommendations shared by us.17 However, as I went through the article, I noticed that many of his objections were actually already answered in our published material, including articles and videos. This means that he is either dishonestly presenting information while knowing the answer, or actually did not engage with the material he is critiquing and is arguing from a position of prejudice against Rasputin. Both alternatives are concerning. Having said that, let’s head over to Davis’ first section on Rasputin.

The Rasputin Affair

First, we must first consider the nature of Rasputin’s supposed crimes.

Historians have ruled out the more heinous allegations that have been leveled against him over the years. Rasputin did not practice black magic. He was not a Khlyst. He did not hold orgies with young nuns. He certainly did not have an affair with the Tsaritsa. Rasputin’s apologists are correct to dismiss these charges as Bolshevik propaganda.

This is mostly correct, however a small change could be made towards the end. The truth is that these were in fact examples of aristocratic propaganda leveled against Rasputin that the Bolsheviks later adopted to delegitimize Tsarist Russia.18

However, there are four credible accusations that may be leveled against Rasputin:

1. Drunkenness. Rasputin was said to be overly fond of vodka.

2. Womanizing. He was widely accused of taking sexual advantage of his followers.

3. Peddling influence. Some contemporaries accuse Rasputin of profiting from his access to the Romanovs. Specifically, he’s said to have secured posts for his “friends,” both in the Church and the State, in exchange for money and/or sexual favors.

4. Political meddling. Rasputin was widely blamed for some of St. Nicholas’s most disastrous policy decisions.

5. Religious charlatanism. Rasputin may not have been the great holy man that he claimed to be.

These are the accusations brought out against Rasputin. Davis claims there are four credible accusations but lists five. We won’t address them for now, first let’s see what he writes about each of them.

Now, to be clear: I’m not saying that Rasputin is guilty of these crimes. (Not at this stage, anyway.) I’m saying that these accusations will prove more difficult for Rasputin’s apologists to dismiss, as they are leveled by more credible sources and supported by more hard evidence.

So, how do we decide whether or not such allegations are true? Let’s consider the credibility of our witnesses.

One would think that he would analyze each allegation carefully and in numerical order to prove his point, as we are doing in this response. Instead, however, he vaguely mentions some of these allegations as he writes, with shallow analysis and no source citations. This is not serious historiography. Why even mention the allegations if you won’t address them seriously?

Rasputin’s critics and defenders face a certain difficulty in this regard. The following points are all true:

• Rasputin was loved by a number of holy men and women, including the Royal Martyrs.

• Rasputin was hated by a number of holy men and women, including St. Elizabeth the New Martyr, St. Benjamin of Petrograd, and St. Mardarije Uskokovic.

• Rasputin was adored by disturbed and evil people like Olga Lokhtina.

• Rasputin was despised by disturbed and evil people like Sergei Trufanov.

This is why I find it problematic when an individual like Davis — who is largely ignorant on the subject matter — declares himself the ultimate authority or “the final word on the matter.” Davis is listing names he read on Douglas Smith’s book without knowing the historical context behind them other than Smith’s incomplete analysis.19

Let’s explore each point in order.

Rasputin was loved by a number of holy men and women, including the Royal Martyrs.

This is true. Some of these holy men and women include Saint John of Kronstadt, Elder Nikolay Guryanov, Saint Augustine (Pyatnitsky), Mother Maria of Helsinki (Anna Vyrubova), Tsar Saint Nicholas II, Tsarina Saint Alexandra, Saint Olga, Saint Tatiana, Saint Maria, Saint Anastasia, and of course Tsarevich Saint Alexei.20

Rasputin was hated by a number of holy men and women, including St. Elizabeth the New Martyr, St. Benjamin of Petrograd, and St. Mardarije Uskokovic.

This is exaggerated. Some holy men were deluded into believing lies against Rasputin, yet this proves nothing about Rasputin’s true character.

Saint Elizabeth, for example, is a favorite among anti-Rasputinites for her intense dislike of the strannik. In fact, Saint Elizabeth disliked Rasputin so fervently that she congratulated Dmitri Pavlovich and Felix Yusupov on carrying out his murder.21 However, what is not usually mentioned is the fact that Saint Elizabeth never met Rasputin in person.22 Her opinion of Rasputin was based on scandalous articles she read on the newspapers and rumors spread by those close to her. For example, Theophan, Bishop of Poltava (who Davis mentions about twenty times throughout his article) became one of those slanderers who misled Saint Elizabeth. Theophan himself was misled by a false confession from a woman. This '“confession” depicted Rasputin as a dangerous sexual deviant. The confession turned out to be false, which evoked great criticism from Hegumen Seraphim (Kuznetsov), as Theophan decided to break the confessional seal to tell the Tsarina about Rasputin’s alleged misdeeds. In Seraphim’s words, “[Theophan (Bystrov)] accused Grigory Rasputin of indecent behavior after a woman’s confession. Here, Bishop Theophan demonstrated his spiritual inexperience by taking the woman’s word for it, which later turned out to be a fabrication.”23 However, Saint Elizabeth believed her spiritual mentor’s errors and became prejudiced against a man she never met. Elizabeth and Theophan were also influenced by newspaper articles framed as “confessions” by women who had allegedly been wronged by Rasputin. One of these articles was titled “Grigory Rasputin and Mystical Debauchery,” written by Martyr Mikhail Novoselov. Saint Mikhail was an ardent anti-Rasputinite, which led him to write slanderous and salacious articles against him. In fact, these articles were so graphic in nature that the Tsarist government had to confiscate them under the anti-pornography laws of the Russian Empire.24 It was a grave spiritual mistake for Theophan and Elizabeth to be influenced by pornographic articles written by another holy man who allowed allegations about Rasputin to influence his perception of the truth.25 Freemason26 Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich, who hated Rasputin due to his anti-war stance,27 also influenced Saint Elizabeth by showing her forged reports of Rasputin’s lascivious behavior.28

It is very unfair to claim that Saint Benjamin (Kazansky) hated Rasputin. The only record I could find of this allegation is from Vladimir Moss’ The Russian Golgotha where Moss claims that Saint Benjamin “[spoke] out openly against Rasputin.”29 I wouldn’t be surprised if Saint Benjamin at some point in his life criticized Rasputin, but there seems to be insufficient evidence to claim hatred.

In the past, I have argued against the idea that Saint Mardarije hated Rasputin based on the unreliability of Stepan Beletsky’s testimony regarding their relationship.30 However, with the release of Mardarije’s memoirs Incomprehensible Russia, I do believe he disliked Rasputin.31 This was probably due to two reasons:

Rasputin was anti-war. Saint Mardarije was a panslavist who supported war with Germany to free the Slavs from the German yoke. This led to a direct conflict with Rasputin, who preferred to avoid a disastrous war. However, Mardarije states in his memoirs that he spoke negatively about Rasputin before they even met, which suggests unjustified prejudice.32 Mardarije held the belief that Rasputin wanted vengeance, while the truth is that Rasputin simply found him somewhat suspicious since Mardarije enjoyed frequenting high-class gatherings and had strong political opinions.33

Rasputin was an enemy of Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich. This Freemason Grand Duke despised Rasputin but was actually friends with Saint Mardarije.34 Hence, in support of Grand Duke Nikolai, Mardarije waged a smear campaign against Rasputin. It’s interesting to note that Saint Mardarije’s memoirs were only recently discovered and heavily edited.35 In Chapter XXV, Mardarije cites an alleged telegram sent by Grand Duke Nikolai, threatening to hang Rasputin for asking to pray with and bless the troops. According to historian Sergey Fomin, this phrase was probably never uttered by the Grand Duke but was just a rumor circulated (perhaps by British Ambassador George Buchanan) to give Nikolai Nikolaevich legitimacy as a brave anti-Rasputinite.36 This theory seems to be in accordance with Military Priest Georgy Shavelsky’s memoirs.37 Either Saint Mardarije wasn’t immune to the propaganda of the time,38 or his memoirs have been maliciously edited. We think it’s probably the former, as was the case for many well-intentioned people at the time, but the latter possibility is nonetheless concerning.

Rasputin was adored by disturbed and evil people like Olga Lokhtina.

It is fair to claim that Lokhtina became disturbed and even crazy for some time. To claim she was evil, on the other hand, is incredibly unfair and ignorant. Since Davis does not tell the reader anything about Lokhtina other than her being “evil” (she is not mentioned again in the article) we will briefly provide historical context. Olga Lokhtina was one of Rasputin’s female followers who was introduced to him by Archbishop Theophan.39 She became one of his most loyal supporters after Rasputin healed her of Neurasthenia Gastrica, just another example of his gift of healing.40 However, to Rasputin’s dismay, in 1911 she was influenced by Iliodor41 into acting like a “Fool for Christ.”42 Being aware of Iliodor’s corruption, Rasputin prohibited this completely, but Lokhtina did not heed his advice and became completely irrational.43 Under Iliodor’s advice, she was forced to abandon her family and act like a fool, which caused her relatives to start avoiding her. In fact, the only person who did not turn away from her was Grigory Rasputin, preventing her from becoming a complete social outcast.44 Grigory continued helping the unstable Lokhtina for years, until an episode when she gravely insulted Rasputin’s wife Paraskeva, which caused Lokhtina and Rasputin to separate.45 In a fit of madness and desperation, she went to see Iliodor at the Florishchev Hermitage, where she was simply turned away due to her “insanity.” She lived with Elder Macarius at the Verkhoturye Monastery for a while in a state of hopelessness, until receiving news of the assassination attempt on Rasputin in 1914. After learning of Iliodor’s involvement in this plot, she recovered completely and became spiritually sound, bitterly regretting her actions against Rasputin. In 1916, Rasputin visited the Verkhoturye Monastery and found Olga Lokhtina “carrying firewood for him, cleaning his cell, praying incessantly, dressed all in white, with icons on her chest.”46 In 1917, she was arrested by the Provisional Government and questioned about her relationship with Grigory Rasputin as part of an official state investigation. The Provisional Government profoundly despised Rasputin and even had his body burned months after his death.47 Despite this prejudice and the fact that her life depended on it, Lokhtina defended Rasputin during the investigation, stating that he was an Elder of God. In her own words, "I have experienced the power of his sanctity on myself, so for me now everything is closed."48 Her fate after this is unknown. To conclude, she could hardly be called an “evil” woman, and her disturbance was not caused by Rasputin but by his enemies.

It must be noted that Davis only mentions Iliodor’s name twice in his whole article.

Rasputin was despised by disturbed and evil people like Sergei Trufanov.

Very true. In fact, we have written a whole article on Rasputin’s greatest enemy, the Apostate Sergey Trufanov. We recommend reading it, as Davis provides no historical context for this notorious character in Russian history.49

So, for every quote about Rasputin’s great sanctity, there’s an equally weighty quote about his depravity. For every madman who said he was God, there’s one who said he was the Devil.

This is a dishonest way to frame the views people held of Rasputin. The idea that Iliodor’s testimony is equivalent to that of Anna Vyrubova,50 for example, is preposterous. Not all quotes are equally weighty.

At the same time, we may note one consistent pattern.

The early-20th century Russian elite had a spiritually adventurous streak. Many were involved in spiritualism, theosophy, and other such un-Christian practices. For many others, a sincere Orthodoxy was mixed with a weakness for pseudo-mysticism and other forms of quackery. Unfortunately, the Tsaritsa was an example of the latter, as evidenced by her early friendship with the French occultist Nizier Anthelme Philippe.

Davis is now trying to convince us that the Tsarina was spiritually weak and naive. For this asinine allegation, he cites the Tsarina’s friendship with Nizier Anthelme Philippe. Describing him as an “occultist” is an incredibly unfair characterization of a humble and devout Catholic man. Historian Sergey Fomin investigated the character of Nizier Anthelme Philippe and concluded that he, like Rasputin, was slandered by jealous aristocrats.51 I personally interviewed Father Andrew Phillips, author of the book A Life for the Tsar: Gregory Efimovich Rasputin-Novy. Fr. Andrew thoroughly explained the historical truth about Nizier Anthelme Philippe, which I will include in the footnotes.52 According to the Orthodox Monk Thomas (Фома Бэттс), Philippe condemned hypnotism and magic due to his Christian faith.53 In fact, he said that to be healed one should ask God and urged people to keep Christ’s commandments.54 Regardless of any shortcomings he may have had, Philippe was undoubtedly a well-intentioned Christian and not an occultist or charlatan.

Davis succeeds in slandering the Tsarina as spiritually immature and a devout Catholic man as an occultist quack.

Rasputin’s supporters tended to be drawn from the ranks of these “adventurers.”

Davis borrows the word “adventurer” from page 42 of Smith’s book, his only source of information.55 This is probably a reference to the Russian word “авантюрист” literally translating to “adventurer” but also meaning “chancer” or “conman.”

Meanwhile, the more traditionally Orthodox elements of society tended overwhelmingly to oppose him. Indeed, as we shall see, the political fallout regarding Rasputin was by far the worst in conservative circles.

This is a baseless assertion which Davis fails to prove in his article. No evidence cited at all.

Having said that, let’s consider the evidence from Rasputin’s life.

Some of his contemporaries claimed that the young Rasputin was a drunk, a womanizer, and a thief. Subsequent historians have taken this more or less for granted. Many have even bought into the idea that his surname was actually a nickname: a play on the Russian rasputni, meaning “degenerate.”

None of this is true, however. Rasputin’s family acquired their name when they moved to Siberia, and there’s no evidence that it reflected on their low moral character. Moreover, the young Gregory had no major run-ins with the authorities.

All of this is true, no objections here. Rasputin’s name actually derived from the word rasputiye, which means crossroads, and was given to those who lived “at the parting of the roads,”56 “which provided access to either Tyumen to the west or to Tobolsk in the northeast.”57

All credible sources suggest that Rasputin began his life as an ordinary peasant, marrying and having children at a young age. Then, quite suddenly, he embraced the life of a “wanderer,” like the narrator of Way of the Pilgrim. He gained a reputation for his magnetic personality, his earthy preaching, and his piercing insight into the human condition.

This is also correct and has been explored thoroughly in our article The True Religion of Grigory Rasputin.58

Still, there were early signs that Rasputin might wander off the difficult path:

1. He effectively abandoned his family to become a “pilgrim.”

He did not abandon his family. While he did go on several pilgrimages that would keep him away from home (sometimes for years) during the 1890s, he would always return back to Pokrovskoye to be with his family. Friends of Rasputin in the village would help the family with whatever they needed while Rasputin heeded his calling as a pilgrim, and his wife was proud that her husband was “the elect of God.”59 After discovering his duty to serve the Tsar, he abandoned his wanderings and spent long periods of time in Saint Petersburg. He saw his family often and ensured their safety and survival. They all outlived him, as their time together was cut short by his brutal martyrdom in 1916.

2. He never submitted to the authority of a spiritual father. Indeed, he was constantly at odds with several bishops of the Orthodox Church.

This is not true. Rasputin’s spiritual father was Elder Macarius of Verkhoturye.60 As for his conflict with “several bishops” (who aren’t named), the truth is that some priests liked him and some didn’t.

3. He had a habit of stroking and kissing his female acolytes.

This is presented with some sort of sexual connotation, but it was just Grigory Rasputin’s way of greeting people. He held people’s hands while talking about spirituality and sometimes kissed them as a greeting, always in an appropriate manner. Some people accused him of acting inappropriately towards women and investigations were launched, all of which failed to prove these scandalous allegations.61 All his female followers confirmed this in their depositions.62

So, knowing what we know about Rasputin’s early life, he definitely would seem vulnerable to the sins of which he is accused: pride, lust, etc.

What do you know about Rasputin’s early life? How can you so confidently declare that Rasputin would seem vulnerable to the sins of pride and lust?

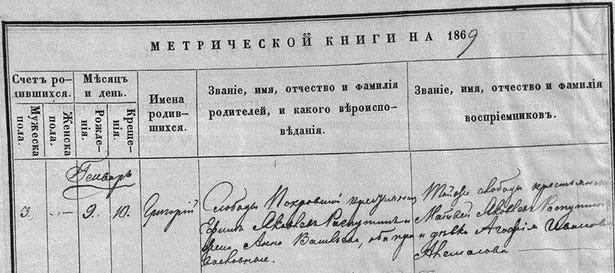

What we actually know about Rasputin’s early life is that he was an Orthodox Christian, baptized one day after his birth and named after Saint Gregory of Nyssa.

Rasputin was described as having a gift of healing during his youth, which he would exercise to heal humans and animals in the village.63 In 1912, he spoke of his youth to a reporter from the Novoye Vremya newspaper: “In summer in my village, when it was warm and sunny and birds sang Edenic songs, I walked down the path and didn’t dare to walk in the middle of it. I dreamed about God, my soul was willing afar. I was crying and didn’t understand the meaning of my tears. When I got older, I often talked to my friends about God, about nature, about birds. I believed in good and kind things and often listened to old men about the lives of the saints, about great deeds, about the terrible and merciful Tsar. So my youth went in a kind of contemplation, in a dream, and then when life touched me, I hid in the corner and prayed secretly. I was unsatisfied and sad.”64 Clearly, Grigory Rasputin’s youth was marked by ardent zeal in the Russian Orthodox Faith, and signs of his gift of healing started to show. Davis doesn’t care to mention that, however. Instead, he moves on to the following section.

Rasputin and the Romanovs

Russia in the 20th century was awash with wanderers and startsy like Rasputin. What set him apart? What brought him to the Romanovs’ attention?

Rasputin represented the profound connection between the common Russian man and the monarchy, which angered the jealous aristocrat usurpers.

Many say that Rasputin healed Tsarevich Alexei’s hemophilia. That’s entirely wrong, however. St. Alexei was never healed of his hemophilia. At most, Rasputin was able to curb his worst “bleeding spells.” That in itself is noteworthy: when saints heal a disease, they actually heal it. They take the illness away. I’m not aware of any who merely offered temporary relief for symptoms.

Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians details that some people may be given “gifts of healing” (in plural).65 That is to say, not all gifts of healing are the same, nor do they manifest equally in all people. It is true that Alexei was never truly healed of his hemophilia, but perhaps it was God’s providence to allow Alexei to survive in order to accompany his family to their martyrdom, faithfully bearing the cross of his disease. Indeed, it is undeniable that without Rasputin, Alexei would have died way before 1918. It is also important to note that Rasputin did heal many people completely, such as Anna Vyrubova, who almost died in a train accident in 1915. While the doctors believed she “was a hopeless case,”66 Rasputin said “She will live” and so she did.67 He also healed Olga Lokhtina, as we already mentioned, as well as Lili Dehn’s son of a high fever.68 Historian Igor Evsin has compiled several miracles attributed to Rasputin in his book “Grigory Rasputin. Insights, Prophecies, Miracles” (Григорий Распутин. Прозрения, пророчества, чудеса). These include the miraculous healing of sick people, prophecies about the future, and several myrrh-streaming icons69 of Grigory Rasputin.70

Indeed, shortly after he met the Romanovs, Rasputin "prophesied" that Alexei would be cured of his hemophilia when he was thirteen years old. Of course, it was in his thirteenth year that St. Alexei was martyred by the Bolsheviks.

I am not aware of this prophecy, nor have I found any credible record of it. Alleged prophecies by Grigory Rasputin should always be analyzed with skepticism, as many come from the corrupt “memoirs” of Aron Simanovich.71

In any event, it does appear that Rasputin was able to stop Alexei’s bleeding spells. However, this could easily be explained by the fact that he prevented the Tsarevich from receiving aspirin. In the early 20th century, Bayer marketed their new drug as a “cure-all.” The Romanovs’ doctors tried using it to treat Alexei’s hemophilia; what they didn’t know is that aspirin is a blood thinner. Rasputin told the Tsarina not to let physicians “bother” Alexei; in this sense, he stopped them from administering an anticoagulant to a hemophiliac. That would explain why the boy’s condition seemed to improve when Rasputin entered their life.

Stress severely exacerbates hemophilia as well. Rasputin was known to have a calming effect on Alexei—indeed, on all children. However, there is no reason to attribute this healing power to supernatural causes. Even more “scientific“ theories (e.g., that Rasputin studied hypnotism) are unnecessary. When a little boy is sick, he naturally turns to his mother for comfort. St. Alexei’s bleeding spells made St. Alexandra extremely distraught, however, and St. Nicholas found it difficult to console either of them. Rasputin may have been the one calm, reassuring presence in Alexei’s little world.

So, there’s no reason to attribute any supernatural origin to Rasputin’s “healing powers.”

Rasputin’s effect on Tsarevich Alexei can’t be reduced to personal speculation about Rasputin’s medical recommendations. The truth is that no doctor in the Russian Empire knew how to treat Alexei for his disease, yet Rasputin, through his prayers, managed to save his life multiple times. In October, 1912, Alexei suffered an incident which left him bed-ridden and in need of surgery, which was virtually impossible due to his hemophiliac condition. Doctors did not know what to do and his condition continued deteriorating, his temperature rising by the hour. Alexei, sure that he would die, asked the Tsarina, “When I am dead, it will not hurt anymore, will it, Mama?”72 Then, on October 22, Grigory Rasputin sent a telegram to the Tsarina, saying: “God has seen your tears and heard your prayers. Grieve no more. Your son will live.”73 The next day, the Tsarevich’s temperature fell and his condition continued improving until he was completely healthy again. Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, the sister of Nicholas II, would testify the following: “An hour later, my nephew was out of danger. Later that year, I met Professor Fedorov, who told me that the healing was completely inexplicable from a medical standpoint. Rasputin definitely possessed the gift of healing. There is no doubt about it. I saw these results with my own eyes, more than once. I also know that the most renowned doctors of the time were forced to admit it.”74

Similarly, Rasputin’s divine gifts permitted him to realize when the Tsarevich was in danger. For example, at one point a strange powder was administered to Alexei by Saint Anna Demidova as part of his treatment. This powder was secretly given to Anna by a member of the Imperial Family who said that it had healing powers and came from the Holy land. Anna believed that the powder was helping Alexei, since he would often go to sleep after it was applied. Rasputin, however, sensed that something was wrong and asked to analyze the powder, which turned out to be poison. This discovery was kept secret to avoid any more schemes against Alexei, but the Romanovs became suspicious of their extended family.75

It’s worth noting that St. Nicholas apparently admitted to having doubts about Rasputin and yet allowed his influence over the Tsaritsa to grow unchecked.

This is a common belief, even among supporters of the Tsar. However, there is absolutely no credible evidence for the idea that Nicholas did not like Rasputin, while there is overwhelming evidence proving the opposite.

Consider the following anecdote by Maria Bok, the daughter of Pyotr Arkadievich Stolypin, who served as prime minister from 1906 until his assassination in 1911. Stolypin was deeply suspicious of Rasputin and urged the Tsar to banish him from the Palace. “I agree with you, Pyotr Arkadievich,” St. Nicholas replied, “but better ten Rasputins than one of the empress’s hysterical fits.”

This is not an authentic quote. For starters, the Tsarina’s “hysteria” was an anti-Tsarist aristocratic myth that began among A.V. Bogdanovich and other decadent socialites.76 Those who knew the Tsarina personally, including Vladimir Sukhomlinov,77 Elizaveta Ersberg,78 and Sergey Kryzhanovsky, among others,79 attest that she had a stable character and warm personality. The idea that her husband thought any different is preposterous. We have their correspondence and diaries. The confusion comes from Maria von Bock’s memoirs, published in New York in 1953.80 This was more than 30 years after the revolution and consists of her quoting her father quoting the Tsar. The actual problem lies, however, in the fact that historians have discovered where this quote came from originally, and it was not from the Tsar’s mouth. The source from which von Bock took this phrase and attributed it to her father is a tabloid exposé published shortly after the February Revolution titled: "Better a Hundred Rasputins Than One Hysteria."81 This phrase was widely circulated, thus constituting trivial political folklore rather than true history. It is known that Tsar Nicholas died wearing a cross gifted to him by Rasputin.82 Likewise, while in exile in Tobolsk, Nicholas asked Dr. Vladimir Derevenko to secretly bring him a little box containing “the most valuable thing for them.” Putting his life at risk, Dr. Derevenko granted the Tsar’s wish. When giving the box to the Tsar the Doctor asked about what was inside, thinking it contained valuable jewels. “This is the most valuable thing for us – the letters from Grigory”, responded the Tsar.83 It is absurd to think that this same Tsar actually hated Rasputin and considered his wife to be hysterical.

On another occasion, Stolypin is said to have presented the Tsar with a dossier chronicling Rasputin’s many moral infractions. Nicholas essentially told the Prime Minister to mind his own business: “I know, Pyotr Arkadievich, that you are sincerely devoted to me. Perhaps everything you say is true. But I ask that you never again speak to me about Rasputin. In any event, there is nothing I can do.”

Once again, another inauthentic quote fabricated by an enemy of the Russian throne. This time, it’s the subversive Vasily Gurko and his book Tsar and Tsarina.84

Vasily Gurko was part of the traitor Generals to the Tsar,85 rejecting his order to send troops to Saint Petersburg in order to prevent unrest in 1917.86 According to historian Pyotr Multatuli,87 Gurko was one of the orchestrators of the February Revolution.88 Clearly, Gurko’s objective in fabricating this quote was to portray Tsar Nicholas II in a negative light, perpetuating the myth that he was a weak and incapable ruler. It is important to note that this source is a third-party citing a conversation not recorded anywhere and does not align with the Tsar’s character and attitude towards Rasputin.

This conversation allegedly occurred in 1911. In June of the same year, Tsar Nicholas wrote in his diary, “After dinner, we had the joy of seeing Grigory upon his return from Jerusalem and Mount Athos.”89 These are clearly contradictory statements. So, who is more credible? Tsar Nicholas in his own words, or the testimony of an anti-Tsarist subversive who — according to the most prominent Nicholas II biographer — was one of the masterminds behind the February Revolution?

Many have looked at this evidence and concluded that Nicholas was simply weak-willed. That’s not true, however. Rather, it seems the Tsar had a difficult time making up his mind about Rasputin. At one point, he supposedly told a courtier that Rasputin “is just a good, religious, simple-minded Russian. When I am in trouble, I like to have a talk with him and invariably feel at peace with myself afterwards.”

Davis only thinks that the Tsar was undecided on Rasputin because he is sharing fake quotes. This quote, however, is real and comes from the actual correspondence of Nicholas and Alexandra.90 For this, Davis seems to be almost directly quoting Orlando Figes.91 This quote from Nicholas II clearly contradicts the other fabricated statements.

The trouble is that Rasputin came to be seen as the power behind the Romanovs’ throne. It was known that Alexandra urged her husband to follow Rasputin’s advice on an absurd range of subjects, from food and transportation policy to land reform to military strategy.

The idea that Rasputin gave advice to the Tsar on everything is exaggerated. However, it is true that Rasputin sometimes gave the Tsar advice beyond matters of faith. In fact, Oleg Platonov analyzed Rasputin’s military and political advice and found it to be quite successful when implemented.92

Whether Nicholas ever took this advice is debatable.

This is not debatable at all. The idea that Rasputin had much political influence was created by the enemies of the Tsar to portray him as a weak ruler.

“Historian S. S. Oldenburg93 specifically traced how Rasputin’s political advice was actually implemented. The results were as follows:94

Rasputin (6 April 1915) advised the Sovereign not to travel to Galicia until the end of the war. The trip nevertheless took place.

Rasputin (17 April 1915) advised against convening the State Duma. The Duma was convened.

Rasputin advised (15 November 1915) that an offensive should be launched “near Riga.” Needless to say, no such offensive occurred.

On the contrary, Rasputin (15 and 29 November 1915) urged that the State Duma be convened: “Everyone now wishes to work; it is necessary to show them a little trust.” The convocation of the Duma was postponed until February.

Rasputin pleaded (12 October 1916) to “put an end to the useless bloodshed” of the attacks in the Kovel sector. In this matter he coincided with very broad circles, including figures of the so-called “Bloc.” Nevertheless, these appeals once again had no effect whatsoever on military operations.

Rasputin “proposed” Count Tatishchev for Minister of Finance (19 December 1915), General Ivanov for Minister of War (29 January 1916), and Engineer Valuev for Minister of Communications (10 November 1916). The Sovereign simply ignored these “proposals.” He did not even respond to them to the Empress. Incidentally, General N. I. Ivanov was dismissed from his post as Commander of the Southwestern Front around the same time.

Rasputin requested that Samarin not be appointed (16 June 1915) and that Markov not be appointed (23 May 1916). These requests were likewise ignored by the Sovereign.

Rasputin suggested Prince Obolensky as deputy minister to Protopopov and expressed dislike for Kurlov; in practice, it was Kurlov who was appointed.

As Oldenburg notes, all of these recommendations were silently rejected by the Sovereign, who did not wish to hurt the Empress’s feelings. At times, however, a certain irritation broke through. “The opinions of our Friend about people are sometimes very strange, as you yourself know” (9 November 1916).”95

Clearly, despite having strong political opinions, Rasputin did not have much political influence at all. Even those who opposed Rasputin, such as lady-in-waiting Sophie Buxhoeveden, stated that “Rasputine [sic] was not the political power pulling the strings of a political game in which Ministers were his pawns.”96

What’s more important is that he was widely seen as being under Rasputin’s spell, and the Tsar did nothing to dispel those rumors. On the contrary, he often forbade officials to criticize the man in his presence. On several occasions, St. Nicholas even removed Rasputin’s detractors from important posts. For instance, Alexander Samarin was dismissed from the post as Procurator of the Holy Synod after just three months in office, for the crime of criticizing Rasputin (more on this in a moment).

Indeed, he should have reprimanded a holy man — regardless of his innocence — to be on good terms with corrupt subversives.

Alexander Samarin was removed for questioning the Tsar’s authority, not for “criticizing Rasputin.” This corrupt character was friends with the Freemason Nikolai Nikolaevich, who despised Rasputin and eventually betrayed the Tsar.97 Samarin vehemently opposed the canonization of Saint John of Tobolsk, something that was only achieved thanks to a friend and alleged protégé of Rasputin, Bishop Varnava (Nakropin).98 According to historian Anatoly Stepanov, Samarin was removed for interfering in matters that concerned only the Tsar (for example, whether he should receive Rasputin or not, whether he should be friends with him or not).99 This was not a decision for Samarin to make but the Tsar, and his constant questioning of the Tsar’s authority and ability to govern led to his removal.

In fact, when Samarin accused the Tsar of letting an unworthy and evil person (Rasputin) near him and his family, Nicholas calmly replied, “Don't you recognize that Her Majesty and I are people of faith? How, then, could we possibly allow near ourselves a person such as the one you depict Rasputin to be? After all, we are not children."100

So, it’s not true that St. Nicholas tolerated Rasputin because he was afraid to stand up to his wife.

Correct.

It seems the Tsar himself was at least partly convinced of Rasputin’s holiness.

He was convinced enough to die wearing a cross gifted to him by Rasputin and claim that his letters were his most valuable possession.

In any event, he was entirely convinced that any damage Rasputin might do to his reputation was worth the comfort it brought to his wife and son—a tragic miscalculation.

Why would Tsar Nicholas betray one of the few people in the Russian Empire truly loyal to him? This once again is an absurd assertion. And with that unfair statement, Davis moves on to the next section of his article.

Rasputin and the Church

Now we’ll ask whether the attacks on Rasputin’s character are credible.

First, however, we should consider what the burden of proof would look like. Put it this way: Men who abuse positions of religious authority generally don’t abuse all of their followers. That’s an easy way to get caught. Rather, they target a handful of especially devoted and/or vulnerable acolytes.

So, it’s not enough for the Rasputinists to prove that their man had a wholesome relationship with Prince X or Countess Y. Any significant evidence that Rasputin abused his followers would be sufficient to prove that he was a fraud. And, to be sure, the evidence against him is fairly overwhelming.

Here, Davis claims that it would be fair to call Rasputin a fraud if he abused his followers, stating that the evidence for this is overwhelming. As you will see, he will go on to talk about Theophan and Hermogenes, yet the matter of abuse will not be brought up at all (other than a vague allegation). So much for the overwhelming evidence…

The most damning testimony comes from the many Orthodox clerics who initially allied themselves to Rasputin but then turned against him, in particular Bp. Theophan (Bystrov) of Poltava and Bp. Hermogen (Dolganyov) of Tobolsk.

Their testimony is in no way “damning,” but it is true that they were initially friends and later became enemies.

It should be noted that, like many Orthodox clerics, Theophan and Hermogen were predisposed to like Rasputin. The clergy had become alarmed by the popularity of Western occultists among the Russian elite, the Romanovs’ own “Master Philippe” being a prime example. These bishops saw Rasputin as an authentically Russian, genuinely Orthodox alternative. They hoped to find a true staretz to guide the the [sic] Tsar and Tsaritsa back to traditional Orthodox spirituality. They placed all of their hopes in Rasputin—a decision that both men would regret for the rest of their lives.

We have already responded to the Monsieur Philippe slander. Grigory Rasputin was authentically Russian and Orthodox. Theophan was misled and allegedly repented for betraying Rasputin during the emigration in France.101 It is known that Hermogenes repented for his own betrayal, blaming Iliodor the Apostate for manipulating him.102

Theophan was one of Rasputin’s very first supporters. The two even lived together for a time in St. Petersburg. Theophan offered Rasputin entrée among the pious Russian elites. Rasputin, meanwhile, secured Theophan a position as the Romanovs’ private confessor.

There is no historical proof whatsoever to suggest that Rasputin secured Theophan a position as the Romanovs’ private confessor. If he became their confessor around 1905 (as is usually suggested), then Rasputin had no influence at all to make this happen.

Before long, however, Theophan began to worry about Rasputin’s odd behavior. He was especially disturbed by the Siberian staretz's his [sic] habit of kissing and caressing his female followers, and of accompanying them to bath houses.

These were allegations brought out against Rasputin during the 1907 investigation. Rasputin rejected all these accusations103 and no damning proof was ever found. Rasputin would be investigated several other times in the future. All the investigations failed to prove any immorality on his part.104 In Bishop Alexei’s words, Rasputin was unequivocally “an Orthodox Christian” with “spiritual leanings (who) sought the truth of Christianity.” Most importantly, he would confess that suggestions of Rasputin’s impropriety were inspired by “all the enemies of the Throne of the Russian Tsar and His August Family.”105

In 1905, Theophan made a pilgrimage to the monastery in Sarov. He spent a whole night praying in the cell of St. Seraphim, praying for his friend. When he emerged the next morning, Theophan said to the monks: “Rasputin is on the false path.”

Davis here gets the dates wrong, as he misread pages 145-146 of Smith’s book (where he gets the narrative for this story).106 This actually happened in 1909, after Theophan’s trip with Rasputin to Verkhoturye. Theophan’s statement about Rasputin being on “the false path” had to do with his view that Rasputin’s life was too luxurious as he had a piano and bentwood “Viennese’” chairs, not for sexual immorality.107 It must be noted that Rasputin’s life was not very luxurious, and he donated most gifts he received to the Church.108 Theophan likely exaggerated his 1917 testimony, as by then he was convinced that Rasputin was evil.

When he returned to St. Petersburg, he confronted Rasputin about his inappropriate behavior. According to Theophan’s testimony, Rasputin promised to stop. Theophan forgave him and moved on, assuming that Rasputin was simply an ignorant peasant, unaware of the scandal his behavior would cause.

But Rasputin didn’t stop. So, Theophan and another bishop, Met. Benjamin (Fedchenkov) of Saratov, confronted him a second time, accusing him of “spiritual delusion” and threatening to publicly denounce him if he did not repent. Reportedly, Rasputin broke down in tears and vowed once again to change his ways.

In fact, Rasputin humbly begged for forgiveness for offending his accusers (despite having done no wrong)109, yet they had already made up their minds against him. It is worth noting that this whole charade was over Rasputin living in Saint Petersburg and meeting with the Romanovs, not due to alleged sexual immorality.110 The Tsarina defended Rasputin, which led to a final break between Theophan and Grigory. Metropolitan Benjamin despised Rasputin and promoted falsified documents that accused Rasputin of sexual immorality. He repented for this in emigration.111 Additionally, it is important to consider that, often, testimony was fabricated by the Extraordinary Investigatory Commission (ChSK) in order to slander Rasputin and the Romanovs.112 However, we do not even have access to Theophan’s deposition, only “fragments of texts, cut and truncated by E.S. Radzinsky.”113 Hence, this source has been double-edited and is unreliable. It is possible that Theophan himself embellished his testimony by omitting certain details of his relationship with Rasputin, such as the fact that he broke the seal of confession to tell the Tsarina about Rasputin’s “misdeeds.” These misdeeds originated in a false confession which Theophan heard and believed, for which he was rebuked by Hegumen Seraphim (Kuznetsov).114 It is also possible that he invented the stories of Rasputin’s impropriety with women (if he even testified to them), as they contradict Vyrubova’s testimony and all the facts that the Extraordinary Investigatory Commission managed to find.115 There is also the more sinister possibility, as we already mentioned, that all of this testimony was fabricated by the Commission. In any case, Theophan’s testimony as cited by Radzinsky116 is completely unreliable and can’t be used to condemn Rasputin.

He didn’t. And so, at last, Theophan requested an audience with the Sovereign. He and his colleagues in the Holy Synod prepared a comprehensive dossier on Rasputin’s offenses, which he intended to present to St. Nicholas. When he arrived at the Palace, however, he was met by St. Alexandra and her friend Anna Vyrubova, a fellow disciple of Rasputin. Rasputin had outmaneuvered him.

Here, Davis omits certain details. For example, the reason for the audience was to reveal the false confession Theophan heard. However, this act made the Tsarina lose faith in Theophan, as he had broken the seal of confession to spread false accusations against a holy man.117 Theophan’s testimony regarding this episode is laughable, framing it as a debate between the Empress and himself, with Theophan “clearly” coming out victorious. Theophan claimed that he had refuted all of the Tsarina’s arguments, and that these were probably given to her by Rasputin. The idea that Rasputin (who could hardly read and write properly) taught the Russian Empress to speak, and, what's more, to argue with the most learned Bishop of Russia is preposterous.118 It does, however, reveal Theophan’s resentment with Rasputin, even though he only had himself to blame for breaking the seal of confession and losing the Tsarina’s trust.

Theophan next appealed to Met. Anthony (Vadkovsky) of St. Petersburg. Theophan and Anthony passed their dossier to Sergei Lukyanov, then-Procurator of the Holy Synod. Lukyanov, in turn, passed the dossier to Prime Minister Solypin; Solypin then made his brave yet fruitless intervention with the Tsar.

We already explained that this “dossier” was nothing other than false written “confession” documents, invented personal confessions, false reports, and media defamation.119 Davis frames this as a “brave” intervention, when in fact it was just slander. Would Davis accept Rodzianko’s 1912 dossier about Rasputin as truthful as well? What about Dzhunkovsky’s in 1915?120 Metropolitan Anthony (Vadkovsky), for the record, was a virulent anti-Rasputinite who allowed the Church press to disseminate secular articles slandering Rasputin. When Rasputin attempted to explain himself, Anthony refused to meet him. He shared his malicious report with the Tsar, who did not believe him as it was well-known gossip. Anthony became so angry that he had a nervous breakdown and died.121

Shortly after their failed coup, Theophan was dismissed as the Romanovs’ confessor and banished to Ashtrakan. (As an aside: Lukyvanov was also dismissed as Procurator. Remember that his successor, Alexander Samarin, was also fired for daring to criticize Rasputin.)

Theophan was appointed to Astrakhan in 1912, two years after the incident with the Tsarina. In fact, he was promoted as the Bishop at the Simferopol and Tavricheskaya Eparchy in the Crimea in 1910.122 So much for Rasputin’s influence. Lukyanov was removed by the Tsar for being an incompetent subversive,123 not due to Rasputin’s influence (who wasn’t even in Russia at the time).124

After the Revolution, Theophan was nearly driven mad by guilt. He was convinced that, by introducing Rasputin to the Royal Family, he was directly responsible for the Russian Revolution.

It is true that Theophan felt guilt for what happened to the Romanovs. However, this guilt was caused by the fact that he unknowingly helped the enemies of the Russian throne come to power. Likewise, Hermogenes, who will be mentioned by Davis in a second, repented for slandering Rasputin before his death. This was recorded by Maria Rasputina’s husband, Boris Soloviev.125

Next we have Bp. Hermogen. Like Theophan, he befriended Rasputin shortly after the latter’s arrival in Petersburg. However, they had a falling out in 1911. Hermogen presented Rasputin with a catalogue of his misdeeds and demanded his repentance. Rasputin told the Tsar, who likewise ordered that Hermogen be banished to a monastery in Siberia.

Unfortunately, one of Hermogen’s allies—a corrupt monk named Ilyador—responded by leaking a letter that the Tsaritsa had written to Rasputin, expressing her desire to kiss his hands, etc. It was all perfectly innocent; again, no mainstream historian really believes that Rasputin and the Tsaritsa had an affair. Nevertheless, it was taken out of context by scandal-mongers and anti-royalists. As a result, St. Nicholas barred the press from publishing any material that was critical of Rasputin.

A complete study of Hermogenes and his relationship with Rasputin has been published on our website under the title A Russian Judas: The Apostasy of Hieromonk Iliodor. Therefore, we will simply copy and paste what has already been written previously about this topic. Perhaps before calling us out, Davis could have read the article, as his objections on Hermogenes have all been addressed.

For context, Iliodor (Sergey Trufanov) was a monk friend of both Rasputin and Hermogenes. He later started slandering Rasputin due to his megalomania or jealousy, and ended up apostatizing from the faith.126 Iliodor managed to fool Rasputin and Hermogenes into thinking he was a holy man, when in fact he was a blasphemous heretic who despised the foundations of the Orthodox Church and Jesus Christ.127 Convinced that Rasputin was the devil incarnate, or perhaps attempting to paint him as such, Iliodor stole letters from Rasputin’s house sent by the Tsarina.128 He would later creatively edit and leak them to the press and the Duma, insinuating the existence of a scandalous relationship between Rasputin and the Tsarina. In fact, the myth of “Rasputin, lover of the Russian queen” originated from none other than the apostate and traitor Sergey Trufanov. In 1911, Iliodor forced himself upon a woman during confession, attempting to violate her.129 When discovered, the cunning Iliodor quickly reversed the roles and accused the woman, named Madame L., of attempting to seduce him. In the spirit of Potiphar’s wife, Iliodor had the woman declared insane and attempted to have her exorcised, avoiding all responsibility. However, her family denounced Iliodor and made a complaint to the Holy Synod.130 When Rasputin found out, he was outraged and refused to associate with Iliodor anymore, already having suspicions about his former friend’s true character. Bishop Hermogenes and Iliodor invited him for a get-together on Vasilyevsky Island, apparently under the guise of mending their friendship. It must be mentioned that by now, Hermogenes thought Rasputin was a degenerate due to his alleged relationship with the Tsarina, a myth triggered by nonе other than their common “friend” Iliodor and his stolen fabricated letters.131 Iliodor had turned Hermogenes against Rasputin, instilling anger and hatred in him.132 The objective of this reunion was to extract a confession out of Rasputin regarding his alleged sexual crimes. At the reunion, Rasputin was surprised to see Iliodor standing defiantly in front of him. Mitya Kozelsky — a fraudster and crippled heretic who was responsible for spreading propaganda about Rasputin’s alleged scandalous affairs — was also there among other individuals, including priests, writers, and merchants.133 Hermogenes first asked Rasputin to defend Iliodor before the Tsar. Rasputin refused and told them exactly what he thought of Iliodor. The conspirators, seeing that they had no use for Rasputin, decided to dispose of him. Hermogenes began to beat up Rasputin, accusing him of heresy and immorality. Iliodor started attacking Rasputin while Mitya fell into an epileptic fit. A couple other witnesses also joined in the violence. Hermogenes and Iliodor attempted to choke Rasputin, but someone knocked on the door of the room, after which the assailants quickly fled.134 Grigory Rasputin managed to escape and told the Tsar that Hermogenes and Iliodor had tried to murder him. For this, Hermogenes was banished to Smolensk, while Iliodor was confined in the Florishchev Hermitage. Later, Hermogenes realized that Iliodor deceived him, stating: “I did not see that, like Satan who tempted Christ, this truly despicable creature, Iliodor, was circling around me, instilling hatred, stubbornness, and malice in me!”135

The testimonies of Bp. Theophan and Bp. Hermogen (now St. Hermogen the Newmartyr) is important for three reasons.

1. As we said, both men were initially friendly with Rasputin. They were not mere clericalists who resented being upstaged by a layman. On the contrary: they admired his simple, rustic spirituality. Also, Rasputin helped to advance their careers; they had nothing to gain from turning on him—at least, not in worldly terms. Theophan and Hermogen were at least sincere in their belief that Rasputin was a deviant and acted selflessly.

Nobody is arguing that they had something to gain. Rather, they were misled by evil individuals who often did have a lot to gain from the downfall of Rasputin and the Romanovs. Hermogenes and Theophan were undoubtedly sincere in their belief that Rasputin was evil, yet this was due to their pride and spiritual immaturity rather than a correct understanding of Rasputin’s character, as they would both end up admitting later on in their lives.

2. Theophan and Hermogen—along with Benjamin, Anthony, and other members of the Holy Synod—provided actual lists of Rasputin’s (supposed) crimes, both of which included drunkenness and adultery. Moreover, these lists were prepared by men who would conceivably have access to such information. They were not the vodka-fueled ramblings of bored aristocrats.

Leaving aside Davis’ use of ambiguous language when accusing Rasputin of drunkenness and adultery, we must note that these lists were made up of forged police reports and scandalous newspaper articles. These allegations have been thoroughly refuted by Russian historians.136

3. It shows that, quite early in Rasputin’s career, the Tsar placed a de facto ban on any criticism of his wife’s favorite. Church leaders simply were not allowed to voice their concerns about the Siberian staretz. Even if they were brave enough to speak out, how could they spread their warning without help from the press?

After the 1905 revolution, the Russian press was essentially free to publish whatever it wanted. The idea that there was a statewide ban on any publications about Rasputin is self-refuting: your own sources contain examples of media campaigns against Rasputin, such as the case of Saint Elizabeth and Met. Anthony Vadkovsky.

Church leaders did voice their concerns about Rasputin, and were disciplined if their complaints became inappropriate. Additionally, why are you presupposing that Rasputin was someone worthy of criticism and that freedom of the press is a virtue? I don’t believe you would hold criticism of Nicholas II to the same standard (nor should you). However, you claim that preventing unjust criticism of the Tsar’s friend is somehow an example of him banning “criticism of his wife’s favorite.” This despicable statement alone should make any Orthodox Christian disavow your article.

How many people could they tell by word of mouth before the Okhrana came knocking?

The Okhrana was fabricating the reports. What are you even arguing here?

This is the irony of the anti-Rasputin case. Most of the accusations that Rasputin’s contemporaries hurled at him was sensationalist nonsense. Yet this doesn’t prove that Rasputin was an angel. The truth about Rasputin never came out because the relevant authorities—i.e., the bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church—were prevented from speaking out by St. Nicholas himself.

There were three investigations into the history, character, and activities of Rasputin during the reign of Tsar Nicholas II. We have all the documents, including accusations, testimonies, and conclusions available. In addition to that, we have dozens of testimonies from Rasputin’s contemporaries attesting to his life of service and holiness, and also several negative testimonies. All the archival material is available for historians to study, including investigations, memoirs, newspaper articles, and letters. Davis is basically claiming that Nicholas II burned the Library of Alexandria down and this is why we will never know the truth about Rasputin. Maybe read more than 1 (ONE!) book about Rasputin before claiming that the Tsar censored everything and everyone.

With this shameful conclusion to his third section, Davis moves on to the last one. This might be the worst one yet.

Conservatives for Rasputin?

This is why, as many historians have pointed out, the major poilitical [sic] fallout of the Rasputin affair occurred mainly on the political Right. For instance, in 1910, the Moscow Gazette—an ultraconservative newspaper—called for the Holy Synod and its Chief Procurator to investigate this wandering peasant. “The personality of Gregory Rasputin must be brought to light,” it declared, “and this seduction must be stopped.”

Utilizing the Moskovskiye Vedomosti (Moscow News/Gazette) as a source on Rasputin is comical. This is the newspaper that published Mikhail Novoselov’s slanderous and salacious articles against Rasputin. These articles were so graphic in nature that the Tsarist government had to confiscate them under the anti-pornography laws of the Russian Empire.137 These articles called Rasputin a “khlyst” and “sex maniac.”138 We know that he was neither, yet since the Moscow Gazette called itself “conservative” we must listen to whatever slander it published. This is the same narrative that politicians like Guchkov and Purishkevich used to subvert Tsar Nicholas II. They were both considered “ultraconservatives,” yet the former said that he would strangle Nicholas II if he did not abdicate,139 while the latter murdered Rasputin and then collaborated with the Provisional Government.140

Of course, the Synod tried to investigate Rasputin but was prevented by order of the Tsar. Not one but two Procurators tried to have him censored; however, they were removed by order of the Tsar. And the Gazette couldn’t publish a follow-up, also by order of the Tsar.

This was in 1910. Rasputin was investigated in 1907, 1909, and 1912. Nobody stopped them, and they proved nothing other than Rasputin’s innocence.141 We already explained that the Procurators were removed for incompetence.

And the Gazette couldn’t publish a follow-up, also by order of the Tsar.

Novoselov did publish a follow-up in 1912 titled Grigorii Rasputin and Mystical Debauchery,142 but instead of going to the Gazette, he went to Guchkov since his brother owned the Golos Moskvy (Voice of Moscow) newspaper.143 This article was not censored. Guchkov began to attack Rasputin at the Duma, putting unnecessary pressure on Nicholas II.144 This is the same Guchkov that despised the Tsar and wanted to strangle him.

Five years later, Lev Tikhomirov—the Gazette’s editor—wrote in his diary:

“People say that the Emperor has been warned to his face that Rasputin is destroying the Dynasty. He replies: “Oh, that’s silly nonsense; his importance is greatly exaggerated.” An utterly incomprehensible point of view. For this is in fact where the destruction comes from, the wild exaggerations. What really matters is not what sort of influence Grishka has on the Emperor, but what sort of influence the people think he has. This is precisely what is undermining the authority of the Tsar and the Dynasty.”

Rasputin was derisively called “Grishka” by his detractors. This quote is interesting, as Tikhomirov himself states that what really matters is the public perception of Rasputin’s influence. The question, in this case, is who helped create the incorrect perception of Rasputin’s ubiquitous influence in Russia. The answer, clearly, is the subversive press, which he led as editor of the Gazette. It must be noted that Tikhomirov also wrote: “There is no tsar, and no one wants one…”145

Similar feelings of bewilderment swept through the Church, the army, the court, and other royalist bastions. Again, we can’t emphasize this point enough: It was the most conservative elements of Russian society who feared that Rasputin would bring down the monarchy. And, tragically, they were proven right.

Baseless assertions. This is just referenced because I stated that all of the article would be included in the response, even if it lacked substance. No proof at all has been shown that Rasputin brought down the Russian monarchy. If anything, this only helped emphasize the role of the press in subverting the Russian Empire.

Why, then, are so many Orthodox eager to defend him?

Because now we know that, despite malicious slander, he was a good and holy man. You obviously have a different theory, though, so please enlighten us.

The truth is that Rasputin’s apologists tend to be young men who converted to Orthodoxy in the last couple of years.

Ironically, Davis himself is a young man who converted to Orthodoxy from Roman Catholicism in 2024. Conversely, the author and founder of the Rasputin Archive (myself) is a cradle Orthodox Christian. Davis’ point is self-refuting. Fortunately, it is nonsensical, as both Cradles and Converts can and do venerate Rasputin.

No doubt they’re perfectly sincere. They might simply assume that the accusations against Rasputin were fabricated by the Bolsheviks. And, as we said, some of them were!

As we already explained, most of the accusations actually came from the aristocracy and the press, not the Bolsheviks.

Yet if we lay aside the polemics—communist and royalist, Leftist and Rightist—we can’t avoid the conclusion that Rasputin was a fraud and a deviant.

We have proven quite the opposite throughout this response.

It may be hard to believe that two holy people like Sts. Nicholas and Alexandra would be taken in by this huckster. Then again, the Devil is a master of lies and deceit. Christ Himself warned that Antichrists will come with “great signs and wonders; insomuch that, if it were possible, they shall deceive the very elect.”

What even is the argument here? Your claim necessitates that we believe the Romanovs were less discerning than the modern gossip writers you use as sources of information.

Even then, if these young men want to base their whole understanding of history on vibes, they should know that the Orthodox conservatives of the early 20th century were on the anti-Rasputin side, with a few notable (and tragic) exceptions.

Nobody is basing anything on “vibes.” This is quite ironic coming from someone who wrote a whole article about a person after reading a single book.

What “Orthodox Conservatives” are you even talking about? The deceived,146 or the subversives?147 Take your pick.

In closing, I will point out that, in 2001, Patriarch Alexei II (of blessed memory) was asked about the possibility of canonizing Rasputin. “This is madness!” he replied. “What believer would want to stay in a Church that equally venerates murderers and martyrs, lechers and saints?”

This is true and has been addressed in our article The Case for the Canonization of Grigory Rasputin. Patriarch Alexy was simply wrong in this case. This was said by him in response to repeated calls for the canonization of Rasputin, which led to a meeting in October, 2004. Here, the Commission on the Glorification of Saints of the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church discussed several questions of faith and veneration. The results were, among other things, the rejection of any sort of canonization for Grigory Rasputin.

Nevertheless, in 2004, the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church charged Met. Juvenaly (Poyarkov) of Krutitsy with leading a commission to investigate Rasputin’s cause for canonization. Met. Juvenaly correctly advised the Synod against moving forward with his cause, citing the overwhelming evidence of Rasputin’s degeneracy.

This is the Commission referenced in the previous paragraph. Unfortunately, this is often enough for skeptics and anti-Rasputin critics to reject his canonization, yet such ideas only stem from ignorance and lack of research. As part of this commission, a report was submitted by Metropolitan Juvenaly (Poyarkov) regarding the life of Grigory Rasputin. For this report, rather than consulting credible historical sources, the Metropolitan used liberal and Bolshevik sources that slander not only Rasputin but also the Tsar and his family. His two main sources were the book “The Holy Devil” by the anti-Christian apostate Sergey Trufanov (Iliodor), and the fictional memoirs of Vera Zhukovskaya, who never personally knew Rasputin and cited atheist sources of information as part of her work.148 This is “the overwhelming evidence of Rasputin’s degeneracy” that Davis mentions. This report also states that Rasputin was killed by people “sincerely devoted to the Tsar” which we know to be blatantly false.149 In writing this report, Metropolitan Juvenaly not only displayed extreme ignorance and irresponsibility, but also found himself disagreeing with modern Orthodox Christian historiography in favor of liberal and Bolshevik sources. This Orthodox historiography includes the work of Metropolitan John (Snychov) of St. Petersburg, who supported Rasputin. Rather than representing the Church’s authoritative opinion, Juvenaly’s negligent report represented historical ignorance and envy against Metropolitan John and other supporters of Rasputin. This report also knowingly concealed objective archival sources that exonerated Rasputin from the accusations of his slanderers, choosing instead to “repeat slanderous rumors orchestrated by the enemies of Russian Orthodoxy and the Monarchy to undermine the Tsar’s authority.”150 It is no wonder that “radio stations hostile to Russia — the BBC, the Voice of America, Radio Liberty, and Deutsche Welle — unanimously endorsed Juvenaly’s report ‘as an attempt by the healthy forces of the Russian Church to repel reactionaries and obscurantists.’” Juvenaly also condemns the very principle of Monarchy and Autocracy. In his report, he contrasts Orthodoxy and Monarchy, condemning the principle of “unlimited power”.151 He says that the supporters of Rasputin “glorify not Christians who have acquired the Holy Spirit, but the principle of unlimited political power”152 a pejorative reference to the system of monarchy, suggesting that being a monarchist is immoral.

Oleg Platonov, a prominent Russian historian who has studied all the archival sources related to Grigory Rasputin’s life, has provided a long and detailed refutation of Metropolitan Juvenaly’s report, which unfortunately influenced the results of this liberal commission. In summary, the singular opinions of some Church liberals must not influence the Orthodox faithful into ceasing veneration of a holy man such as Grigory Efimovich Rasputin.

Let this be the final word on the matter. And let’s all find a better hill to die on.

This simply cannot be the “final word on the matter.” How prideful can one be to declare himself the absolute authority on a topic he has hardly researched? Historical debate and exploration is fruitful, slander and ignorance is pernicious. The Rasputin Archive project is one of historical truth against the myths that have maligned a holy man for more than a century. These myths were created to destroy the Tsar, discredit the Church, and justify a catastrophe that ended the lives of millions of faithful Orthodox Christians. We will not stop with the historical rehabilitation of Rasputin. What better hill is there to die on?

This is not a personal attack on Davis, but a recognition of this person’s pre-existing biases against Rasputin. These biases reveal his true motivations and are briefly explored in this rebuttal, before looking at the arguments themselves.

Davis, M. W. (2026, January 6). Was Rasputin a saint? Union of Orthodox Journalists. https://uoj.news/history-and-culture/86000-was-rasputin-a-saint

Some of the sources for the article, such as Iliodor’s unreliable book “The Holy Devil” — which served as the primary source of information for Juvenaly’s 2004 report — actually do claim that Rasputin had an affair with the Tsarina.

Anthony recently invited me on for a YouTube livestream, where we discussed the life and death of Grigory Rasputin. You can follow Anthony on X HERE and watch our livestream HERE. This livestream was incredibly successful, receiving thousands of views and hundreds of likes, with many people stating that they had learned a lot of new information about Rasputin.

I believe James is Anglican, so perhaps he is being called out by association. You can watch my appearance on his podcast HERE and on Spotify.

Smirnov, V and M., Rasputin

Evsin, I., Oklevetannyi Starets (The Slandered Elder), p 10

Massie, R., The Romanovs: The Final Chapter, p 8

Mironova, T., Grigori Rasputin: Belied Life – Belied Death

Talabsk.ru. (2017, January 23). Чудесное явление иконы мученика Григория Распутина [The miraculous appearance of the icon of the martyr Grigory Rasputin]. Talabsk.ru. https://talabsk.ru/129-chudesnoe-yavlenie-ikony-muchenika-grigoriya-rasputina.html

Irina Aleksandrovna Vysotskaya, “Григорий Ефимович Распутин оболган,” Русская Народная Линия (Ruskline.ru), August 22, 2018, https://ruskline.ru/news_rl/2018/08/22/grigorij_efimovich_rasputin_obolgan.

This term has been commonly used in a derogatory manner by the likes of Leon Trotsky and other heinous characters.

Kaleda, G. K. (2024). “Rasputin the traitor”: The formation of an image in 1914–1916. History Magazine – Researches, 2, 132–144. https://doi.org/10.7256/2454-0609.2024.2.69949

This propaganda originated in gossip within aristocratic circles and was promoted by anti-Tsarist subversives in the media and Duma. Once the Bolsheviks came to power, they themselves would utilize this propaganda to call the Tsar a tool of Rasputin.

See for example: Rassulin, Y. Y. (2020, July 5). Chapter 10, Parts 6–7. In The great righteous elder passion-bearer Grigory: Grigory Efimovich Rasputin-Novy. Proza.ru. https://proza.ru/2020/07/05/1313

For Lokhtina, for example, see Smith, D., Rasputin: Faith, Power, and the Twilight of the Romanovs, p 282

which does not consider

Materials of the Extraordinary Investigation Commission, acquired by M. L. Rastropovich at Sotheby's auction (London, 1995); cited from: Radzinsky E. Rasputin: Life and Death. Moscow: Vagrius, 2001. pp 198-199. analyzed in Rassulin, Y. Y. (2020, July 5). Chapter 6, Part 2. In The great righteous elder passion-bearer Grigory: Grigory Efimovich Rasputin-Novy.

and Phillips, A. (2016, December 1). St. Maria of Helsinki. Pravoslavie.ru. https://pravoslavie.ru/99085.html

Telegram to Grand Duke Dmitri, 18 December 1916, Byloye Journal, p 82 and Yusupov, F. (I), Konetz Rasputina, p 201 reproduced in Nelipa, M., Killing Rasputin: The Murder That Ended the Russian Empire, Appendix A

Phillips, A., A Life for the Tsar: Gregory Efimovich Rasputin-Novy (1869-1916), pp 36-37 and Fomin, S., Grigory Rasputin: An Investigation, [Volume IX] pp 392-395

Hegumen Seraphim. Orthodox Tsar-Martyr. Moscow, 2000. pp 82-83.

In accordance with Article 1001 of the Penal Code

Sidorov, A. From the notes of a Moscow censor//Voice of the Past, 1918. N 1-3. p 98. Quoted from: Fomin, S. The lie is great, but the truth is greater. Moscow, 2007. p 128.

Fomin, S. The Lie is Great, but the Truth is Greater. Moscow, 2007. p 130

A.I. Spiridovich. Security and Anti-Semitism in Pre-Revolutionary Russia. Questions of History. Moscow, 2003. N8. See also Oleg Platonov. Russia’s Crown of Thorns. The Conspiracy of the Tsaricides. Moscow, 1996. p 514. Sergey Fomin. The Lie is Great, but the Truth is Greater. Moscow, 2007. p 308

A.I. Spiridovich. Security and Anti-Semitism in Pre-Revolutionary Russia. Questions of History. Moscow, 2003. N8. p 23. See also Oleg Platonov. Russia’s Crown of Thorns. The Conspiracy of the Tsaricides. Moscow, 1996. p 514. Sergey Fomin. The Lie is Great, but the Truth is Greater. Moscow, 2007. p 308

These fabrications were made by the Minister of Internal Affairs, A.N. Khvostov, and his deputy, S.P. Beletsky.

Oleg Platonov. Russia’s Crown of Thorns. Prologue to the Tsaricide. The Life and Death of Grigori Rasputin. Moscow, 2001. pp 203-212. Sergey Fomin. The Lie Is Great, But the Truth Is Greater. Moscow, 2010. pp 316-317. Smirnov V., Smirnova M. Unknown about Rasputin. PS Tyumen, 2006. pp 56-57.