A Russian Judas: The Apostasy of Hieromonk Iliodor

"I did not see that, like Satan who tempted Christ, this truly despicable creature, Iliodor, was circling around me, instilling hatred, stubbornness, and malice in me!" Saint Hermogenes Dolganyov

Grigory Rasputin made many enemies throughout his forty-seven years of earthly life. Yet none of them proved more dangerous or more deceitful than Sergey Trufanov, the defrocked monk previously known as Hieromonk Iliodor. The man who started as an apparent friend to Grigory Rasputin ended up being his major enemy, or as Iliodor would say before attempting to assassinate him in 1914: “I am the winner in this battle, and not you, Grigory! … I am telling you… I – am your nemesis!”1

Beginnings

Iliodor, named Sergey Trufanov, was born in 1880 in a small Cossack village near the Don river. At age fifteen, he entered the theological seminary, graduating five years later and moving to Saint Petersburg. He was ordained a Hieromonk in 1903 and graduated from the St. Petersburg Theological Academy in 1905, where he became acquainted with the subversive spy-priest George Gapon.2 George Gapon orchestrated the 1905 Revolution against the Tsar. Iliodor briefly met Grigory Rasputin in 1904, when the strannik complimented him on his method of prayer.3 However, their friendship really flourished around five years later, when Rasputin interceded to stop Iliodor’s transfer from his monastery in Tsaritsyn to Minsk. At that moment, Iliodor stated that “Had any one suggested that I should prostrate myself at Gregory’s feet and kiss them, I should have done so without stopping to think.”4 Grigory and Iliodor became good friends, often talking about religious matters and the importance of the Orthodox faith. Rasputin — perhaps naively or accurately at the time — considered Iliodor to be a devout man of God. In 1914, after an assassination attempt against him incited by Iliodor, Rasputin would painfully recall:“I lived with him amicably and shared my impressions with him.”5 In 1908, Rasputin joined his old friend Bishop—now Saint—Hermogenes Dolganyov, who was already a friend of Iliodor as well. The three became close and met in 1909 to discuss their faith and love for God. Hermogenes was very fond of Rasputin, who he considered to be a man of God and faithful Orthodox Christian. In Hermogenes’ own words: “This is a servant of God. You would be sinning if you even mentally condemned him.”6 Rasputin himself described Hermogenes as a “good bishop [with] a righteous spirit.”7

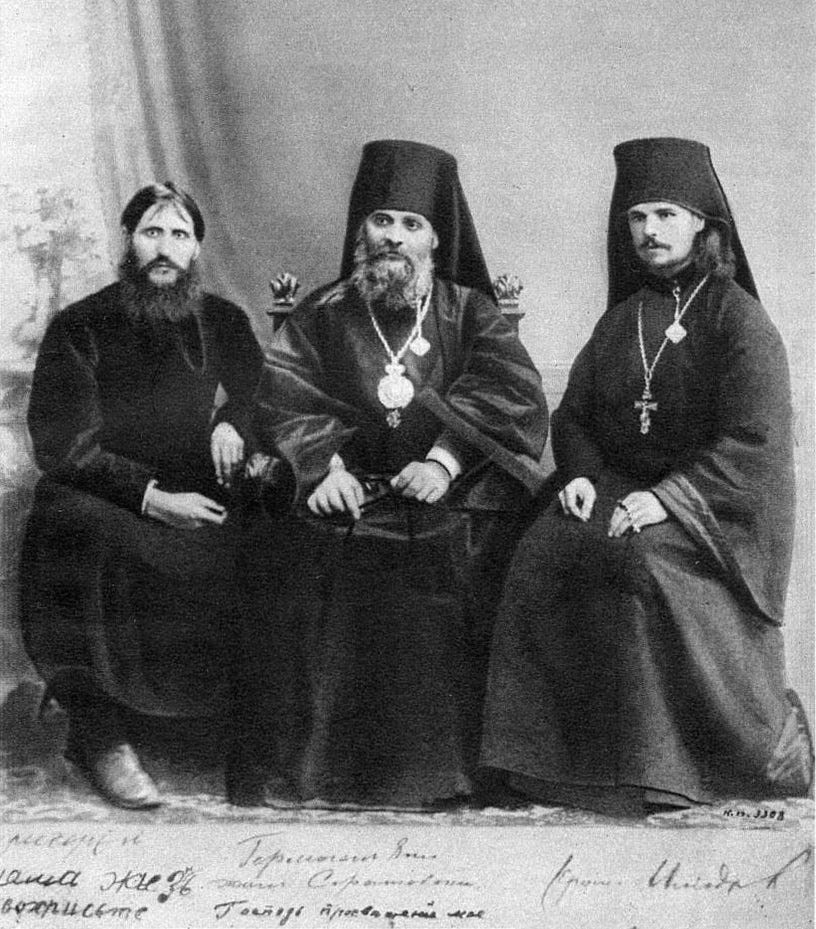

Photograph from 1908 depicting Rasputin, Hermogenes, and Iliodor. Hermogenes wrote, “The Lord is my enlightenment,” Grigory, “Our life in Christ is by God’s providence,” and Iliodor limited himself to writing his name.8

Meanwhile, Iliodor continued to be Rasputin’s friend, yet early signs of wicked disgust started to show in him. Describing his friend Iliodor would recall that “Gregory was dressed in a cheap, greasy, gray coat… His pockets were inflated like those of a beggar… The hair on the saint’s head was roughly combed in one direction; his beard looked like a piece of sheepskin pasted to his face to complete its repulsive ugliness. His hands were pock-marked and unclean, and there was much dirt under his long and somewhat turned-in nails. His entire body emitted an indeterminate, disagreeable smell.”9 Such disdain for a peasant’s humble lifestyle revealed Iliodor’s true character. Following Hermogenes’ orders, Iliodor and Rasputin would visit several homes in Tsaritsyn, helping the poor and needy.10 Iliodor led a monastery in the center of Tsaritsyn, where he acted like a demagogue and provocateur.11 In November 1909, Rasputin and Iliodor went to Pokrovskoye, the former’s homeland, by train. This episode would be mentioned in Iliodor’s scandalous memoirs, where he would creatively invent lascivious stories about the peasant to sell more books and destroy his reputation.12 At Pokrovskoye, Iliodor stayed with Rasputin in his home, which was adorned with icons and crosses.13 Iliodor would visit Rasputin in his village in 1909, 1910, and 1911.

Grigory Rasputin

Falling-out

It was probably in these latter years that Iliodor began to harbor ill feelings towards Rasputin, perhaps due to his megalomania or jealousy. This also coincided with a massive propaganda campaign against Rasputin from the nobility, press, and evil or misinformed church hierarchs. Here the true character of Iliodor must be analyzed, lest anyone believe that his views on Rasputin were justified. Iliodor was a megalomaniac political activist and careerist, who was incredibly eloquent and devious. He managed to fool Rasputin and Hermogenes into thinking he was a holy man, when in fact he was a blasphemous heretic who despised the foundations of the Orthodox Church and Jesus Christ.14 Convinced that Rasputin was the devil incarnate, or perhaps attempting to paint him as such, Iliodor stole letters from Rasputin’s house sent by the Tsarina.1516 He would later creatively edit and leak them to the press and the Duma, insinuating the existence of a scandalous relationship between Rasputin and the Tsarina. In fact, the myth of “Rasputin, lover of the Russian queen” originated from none other than the apostate and traitor Sergey Trufanov. In 1911, Iliodor forced himself upon a woman during confession, attempting to violate her.17 When discovered, the cunning Iliodor quickly reversed the roles and accused the woman, named Madame L., of attempting to seduce him. In the spirit of Potiphar’s wife, Iliodor had the woman declared insane and attempted to have her exorcised, avoiding all responsibility. However, her family denounced Iliodor and made a complaint to the Holy Synod.18 When Rasputin found out, he was outraged and refused to associate with Iliodor anymore, already having suspicions about his former friend’s true character. Bishop Hermogenes and Iliodor invited him for a get-together on Vasilyevsky Island, apparently under the guise of mending their friendship. It must be mentioned that by now, Hermogenes thought Rasputin was a degenerate due to his alleged relationship with the Tsarina, a myth triggered by nonе other than their common “friend” Iliodor and his stolen fabricated letters.19 Iliodor had turned Hermogenes against Rasputin, instilling anger and hatred in him.20 The objective of this reunion was to extract a confession out of Rasputin regarding his alleged sexual crimes. At the reunion, Rasputin was surprised to see Iliodor standing defiantly in front of him. Mitya Kozelsky — a fraudster and crippled heretic who was responsible for spreading propaganda about Rasputin’s alleged scandalous affairs — was also there among other individuals, including priests, writers, and merchants.2122 Hermogenes first asked Rasputin to defend Iliodor before the Tsar to avoid his condemnation, yet he refused and in fact told them exactly what he thought of Iliodor. The conspirators, seeing that they had no use for Rasputin, decided to dispose of him. Hermogenes began to beat up Rasputin, accusing him of heresy and immorality. Iliodor started attacking Rasputin while Mitya fell into an epileptic fit. A couple other witnesses also joined in the violence. Hermogenes and Iliodor attempted to choke Rasputin, but someone knocked on the door of the room, after which the assailants quickly fled.2324 Grigory Rasputin managed to escape and told the Tsar that Hermogenes and Iliodor had tried to murder him. For this, Hermogenes was banished to Smolensk, while Iliodor was confined in the Florishchev Hermitage.

Apostasy

Iliodor lived in the Florishchev Hermitage but soon grew tired of this confinement. Unable to bear a more than deserved punishment, he decided to quit his monastic vows in 1912. Almost theatrically, he wrote a letter to the Holy Synod stating: “I renounce your God. I renounce your faith. I renounce your Church” and signed it with his blood. Iliodor presents this apostasy quite proudly in his autobiography.25 In response, the Church defrocked him. Iliodor, who always attempted to give the impression of a holy man, turned out to be spiritually dead and morally rotten. Apparently, after this apostasy, Rasputin wrote to the Tsar and Tsarina in fear and worry, stating, “Darling Papa and Mama: Iliodor is a horrible devil. A renegade. An accursed one. He must be declared insane. Doctors must be called, or he will prove a calamity. He dances to the devil’s pipes.”26 This would prove to be correct, as Iliodor would later plan a failed assassination attempt on Rasputin in 1914 through a follower of his named Khioniya Guseva. Towards the end of his life, he would become a Baptist who preached that Christ is not God but a simple man born of a simple woman, and that he never rose from the dead.27

1914 Assassination Attempt

In January 1914, the police received information from Ivan Sinitsyn, a former disciple of Iliodor, who stated that Iliodor had begun to plan a “number of terrorist acts” to end Rasputin’s life. Sinitsyn submitted multiple letters written by Iliodor, which revealed that a woman named Khioniya Guseva received a large sum of money. On February 2nd, Sinitsyn contacted the police saying that Iliodor had threatened to murder him for his betrayal. Ivan Sinitsyn died mysteriously after eating fish that same day.28 Another member of Iliodor’s conspiracy later submitted a deposition, stating that he urged them to “gather money to organize Rasputin’s murder.” The police ignored the information.29 A couple of weeks before Germany declared war on Russia, Rasputin was attacked by a stranger in front of his home. It’s a well-known fact that Rasputin was against Russian involvement in WW1 and actively advised the Tsar against it.30 However, during the most important moments, he wasn’t available to advise the Tsar due to his injuries and limited himself to sending telegrams from the hospital, asking him not to engage in the war.31 The attacker was a thirty-three year old woman from Tsaritsyn who stabbed him with a dagger she had concealed under her skirt. Wounding Rasputin in the abdomen, she lunged again to murder him. Fortunately, a stranger who saw what was going on intervened and tackled Guseva to the ground. She was taken to a police station where she quickly confessed her crime, claiming that she tried to murder Rasputin because he was the “antichrist.”32 She was deemed to be suffering from insanity due to late-stage syphilis and emotional scarring after Iliodor’s expulsion from Tsaritsyn. Rasputin was severely wounded and the prognosis was not good. However, due to a combination of quick medical attention and prayer, he made it through. In the words of Bishop Varnava of Tobolsk: “The Lord God will save His faithful servant.”33

Among Guseva’s belongings, letters bearing a signature and a similar writing style to Iliodor’s were found. A note received by Rasputin was presented during the investigation, signed by a man named “Uznik” (prisoner) inferring Iliodor in the Hermitage. This note read: “I am the winner in this battle, and not you, Grigory! … I am telling you… I – am your nemesis!”34 Before he could be questioned, Iliodor quickly fled his home in a car owned by Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolayevich, another anti-Rasputin warmonger and megalomaniac.35 Eventually, the Tyumen Court declared that Iliodor was guilty of inciting murder. By this time, however, Trufanov had already escaped to Norway through the Finnish border dressed as a woman with the help of Maxim Gorky.36 Decades later, Iliodor would confess to the crime in his book Martha of Stalingrad.37 Khioniya Guseva would later be freed by the Kerensky Government and either her or her sister tried to assassinate Patriarch Saint Tikhon in a similar way.3839

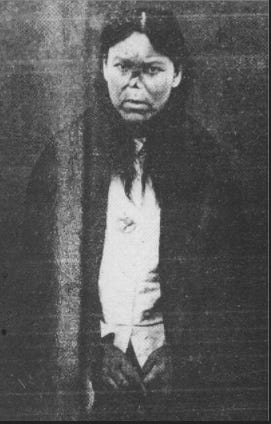

Khioniya Guseva, Iliodor’s pawn in the attempted murder of Rasputin

Conclusion

Eventually, Iliodor escaped Russia and went to America, where he would act in scandalous movies about Rasputin as himself.40 He published his book about Rasputin in America as well, for which he was handsomely rewarded by the Metropolitan Journal in New York.41 After the October revolution, the Bolsheviks published his book as well, demonstrating once again that Rasputin was despised by aristocrats and revolutionaries alike. In the early 1920s, he offered his support to Lenin in building communism, which Lenin promptly ignored. Iliodor saw that he had no future in Russia, and moved definitively to New York. There, he spread stories about how he had been embraced by Lenin and the Bolsheviks in Russia, how he had visited the Romanovs at Ipatiev during Easter in 1918, and how he was actually presented with the head of Tsar Martyr Nicholas II in a glass jar by none other than Khioniya Guseva.42 Throughout the rest of his life, Iliodor was involved in several get-rich-quick schemes, most of which failed. He lost most of his money in the Crash of 1929 and afterwards lost a lawsuit to René Füllöp-Miller.43 His final days were spent working as an impoverished janitor in the Metropolitan Life Insurance Tower in New York City, a fitting end for such a wicked man.44 The story of Iliodor is incredibly important because of the extent to which he could manipulate people around him. Iliodor was so eloquent and cunning that he managed to fool holy men like Saint Hermogenes into despising Rasputin. Hermogenes eventually realized that Iliodor deceived him, stating: “I did not see that, like Satan who tempted Christ, this truly despicable creature, Iliodor, was circling around me, instilling hatred, stubbornness, and malice in me!”45 It has been suggested by historians46 that the two eventually reconciled, yet not much information is available about this. Ultimately, however, Hermogenes recognized his error in trusting the subversive Iliodor, for which he repented bitterly until the day of his martyrdom. Despite this, many Church hierarchs continue to slander Grigory Efimovich Rasputin with information extracted from these types of individuals. It is unfortunate, for example, that Iliodor’s memoirs were the principal source used by Metropolitan Juvenaly in his libelous report for the Commission on the Glorification of Saints of the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church in 2004.47

Such is the story of the man who became, perhaps, Rasputin’s greatest enemy — an apostate, a liar, and a traitor. Like Judas, who saw holiness in Christ our Lord and still decided to betray Him, Iliodor destroyed his only true friend for the sake of his megalomaniac desires for power and fame. And like Judas, who despondently suffered the consequences of his betrayal, may Sergey Trufanov the Apostate enjoy his reward where he rightfully belongs.48

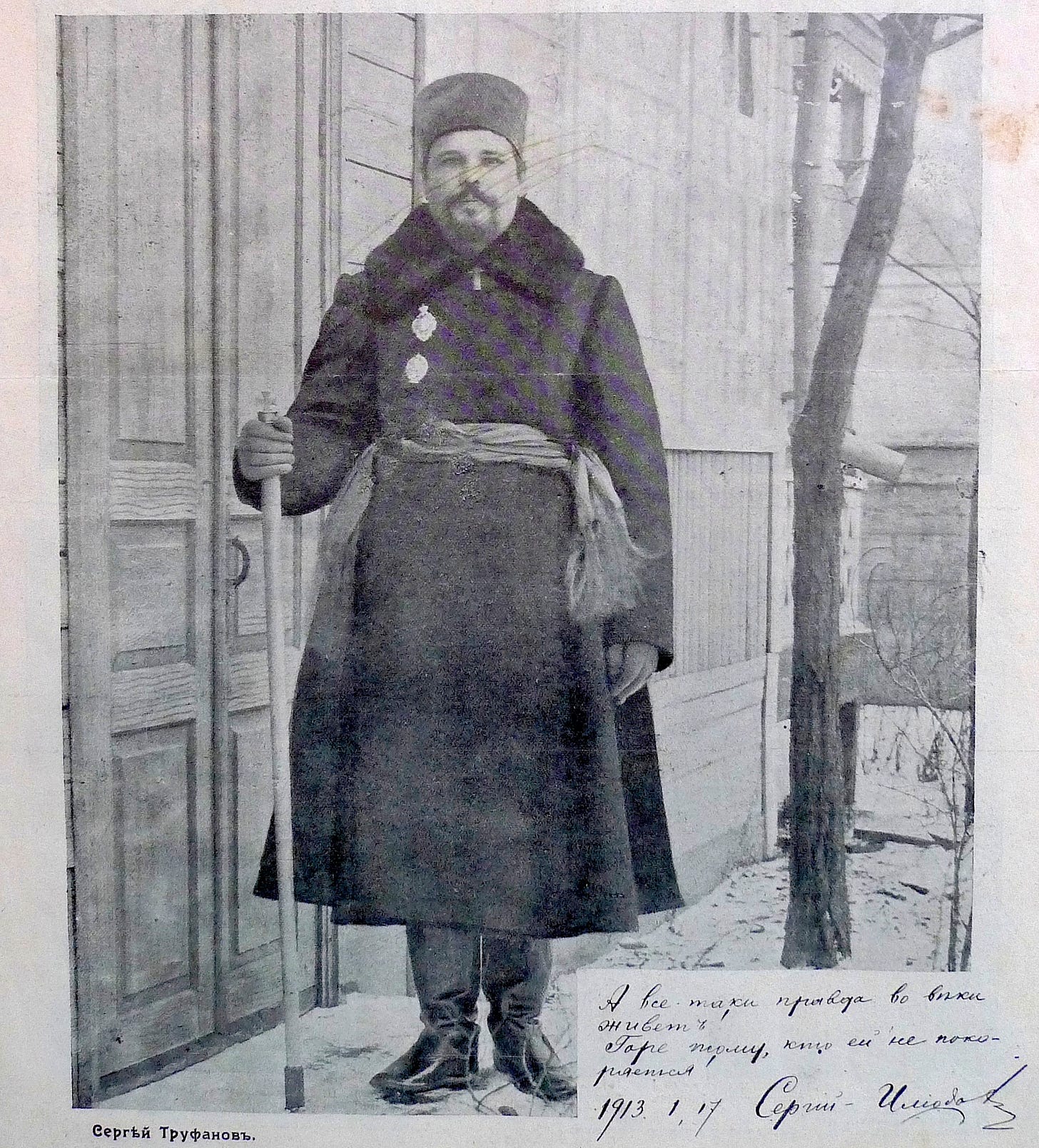

Sergey Trufanov, 1913

Pokazaniya Grigorii Rasputin-Novy, submitted 9 August 1914, reproduced in: Zhizn za Tsarya, p 130

Trufanov, S., The Mad Monk of Russia, Iliodor, p 22

Russian State Historical Archives Op.191. D.143v. L.15 rev. Report of the head of the Saratov Provincial Gendarme Directorate, April 3, 1910.

Trufanov, S., The Mad Monk of Russia, Iliodor, p 98

Testimony of the wounded Rasputin in 1914, reproduced in: Sedova, Yana Anatolyevna. “Иеромонах Илиодор и Григорий Распутин.” Русская народная линия, January 3, 2021. https://ruskline.ru/analitika/2021/01/02/ieromonah_iliodор_i_grigorii_rasputin#_ednref1

Zhevakhov, N. D., Memoirs. Vol. I: September 1915 – March 1917, ch. 61

Hofstetter I.A., Grigory Rasputin as a mysterious psychological phenomenon of Russian history (based on personal memories). Moscow, 2017. p 45

State Archives of the Saratov Region F.1. Op.1. D.8297. L.147. Vasilevsky’s report of March 14, 1910.

Trufanov, S., The Mad Monk of Russia, Iliodor, p 92

Trufanov, S., Святой черт (The Holy Devil), p 22

Platonov, O., Zhizn za Tsarya, ch. 13

His “memoirs” were published in Russia under the title Святой черт (The Holy Devil). Later, they were published in the U.S. as The Mad Monk of Russia, Iliodor.

Nelipa, M., Killing Rasputin: The Murder That Ended the Russian Empire, p 33

Platonov, O., Zhizn za Tsarya, ch. 13 describes Iliodor’s “fall from grace” and examples of his heretical and blasphemous views

Radzinsky, E., The Rasputin File, p 149

Rasputina, M., My Father, p 66

Rasputina, M., My Father, p 67

Ibid.

Nelipa, M., Killing Rasputin: The Murder That Ended the Russian Empire, p 37

N. Kozlov, article “In Memory of the Elder” in the book 1994, G. E. Rasputin - New “Spiritual Heritage”, Galich, 1994, p. 17.

Rasputina, M., My Father, p 68

Sedova, Yana Anatolyevna. “Иеромонах Илиодор и Григорий Распутин.” Русская народная линия, January 3, 2021. https://ruskline.ru/analitika/2021/01/02/ieromonah_iliodор_i_grigorii_rasputin#_ednref1

Trufanov, S., Святой черт (The Holy Devil), p 131

Rasputina, M., My Father, pp 68-69

Trufanov, S., The Mad Monk of Russia, Iliodor, pp 264-265

Trufanov, S., The Mad Monk of Russia, Iliodor, pp 265-266

Platonov, O., Zhizn za Tsarya, ch. 13 describes Iliodor’s “fall from grace” and examples of his heretical and blasphemous views

“Pokusheniye na Gr. Rasputina”, Birzheviye Vedomosti, No. 14232, 2 July 1914, p 2

Nelipa, M., Killing Rasputin: The Murder That Ended the Russian Empire, pp 40-41

Phillips, A., A Life for the Tsar: Gregory Efimovich Rasputin-Novy (1869-1916), p 39

Ibid.

Dopros H. Guseva, June 29, 1914, reproduced in: Platonov, O. (II), Zhizn za Tsarya, pp 122- 123

“Sobitiya dnya”, Novoye Vremya, No. 13757, 1 July 1914, p 2

Pokazaniya Grigorii Rasputin-Novy, submitted 9 August 1914, reproduced in: Zhizn za Tsarya, p 130

Nelipa, M., Killing Rasputin: The Murder That Ended the Russian Empire, p 46

Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolayevich would be instrumental in turning Grand Duchess Saint Elizabeth against Rasputin, even though she never met him in person

Trufanov, S., The Mad Monk of Russia, Iliodor, p 282

Radzinsky, E., The Rasputin File, p 258

Markova, A., Saint Tikhon. Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia

Smith, D., Rasputin: Faith, Power, and the Twilight of the Romanovs, p 678

See: The Fall of the Romanoffs, 1917

Platonov, O. (I), Grigorii Rasputin i Deti Dyavola, p 175

Smith, D., Rasputin: Faith, Power, and the Twilight of the Romanovs, p 677

The lawsuit was over this book in question: Fülöp-Miller, R., Rasputin: The Holy Devil.

Ibid.

N. Kozlov, article “In Memory of the Elder” in the book 1994, G. E. Rasputin - New “Spiritual Heritage”, Galich, 1994, p. 17.

Mainly Igor Evsin, a respected historian in Rasputin-related historiography

For more information, read The Case for the Canonization of Grigory Rasputin

Proverbs 19:5

A false witness will not go unpunished,

And he who speaks lies will not escape.

I recently obtained a second hand copy of The Mad Monk from the original first printing. It is, in my view, an utterly fraudulent and fantastical/nonsensical tale. The only value one may surmise from it is in terms of a historical record, of a man seeming to absolve himself and condemn a friend.